Breeding new potato varieties is easy. You can hand-pollinate potato flowers in far less time than it'll take you to read this article, but I'm going to attempt a reasonably thorough explanation, so I hope you find it helpful.

Potato breeding is done through sexual reproduction, i.e. pollinating flowers to produce berries which contain true seeds (TPS). Normally when you plant potatoes you propagate them from tubers, confusingly called seed potatoes but which are not actually seeds, but root cuttings. You can't cross tubers. They can only reproduce themselves as they are. Occasionally a plant may produce a spontaneous mutation but it doesn't happen often enough to be useful as a breeding method. Flowers are the way to go, because they give you the option to combine and reshuffle genes from the parent varieties of your choice.

There's a lot to be grateful for in the anatomy of a potato flower. Hand-pollinating them is very easy. The flowers are large and easy to work with, and the individual parts are easy to manipulate.

What's not so easy is making careful plans and predictions for what you might get out of it, and that's because potatoes are tetraploid. If you've no idea what I'm talking about then have a look at my previous post about TPS for a simplified explanation. To give a one-sentence summary: a tetraploid has double the amount of genetic material that a normal (diploid) organism has, which is a bit like inheriting traits from four parents rather than two. Tetraploids are a quirk of nature but in potatoes they are a very successful one, and the vast majority of cultivated potatoes in Europe and North America are tetraploid.

You may still come across the occasional diploid. Mayan Gold and its associated varieties are diploid, and those who are growing TPS from Tom Wagner may have a few diploid lines from him. Diploid potatoes can be recognised by a tendency to have smaller and less fleshy leaves, but the most distinctive feature is the berry. A diploid potato berry has a distinctively pointed end, kind of strawberry shaped, while tetraploid berries are more rounded and tomato-like. If you're feeling experimental you can try crossing a diploid with a tetraploid. At best you will only get a few viable seeds out of it, but it's a brilliant way of introducing new diversity into potatoes. At some point soon I will give it a whole article of its own, as it's too elaborate a subject to go into here.

Potato berries (these are tetraploid ones) in development.

However, assuming the potatoes you want to cross are tetraploid, since most of them are, it's very difficult to predict what the resulting offspring will be like because of the genetic variability involved. With tetraploids, the convenient order of the Mendelian ratio is thrown out the window and replaced by something more akin to a gene tombola. F1 hybrids are not uniform as they are in most other types of breeding project. If you grew a lot of offspring from your cross you'd find that many traits show continuous degrees of variation through the population, rather than segregating into Mendel's either/or groups … which happens because there are so many different ways the alleles can arrange themselves. To quote a research paper by Scotland's premier spudmeisters, Meyer et al (1998) "[Tetraploid] inheritance implies the random pairing of four homologous chromosomes at meiosis, and in a highly heterozygous outbreeding species results in a large number of possible allelic combinations at a single locus. In the most extreme case, eight different alleles could segregate independently in a population, resulting in 36 possible genotypic classes in the progeny." In other words, potatoes naturally have a mixed up genepool (from outbreeding) and when they pollinate and set seed those alleles can arrange themselves in any order - with each different combination having a unique effect on how that trait is expressed. And we're just talking about an individual locus here … the same is happening at every other locus throughout the whole genome. Yowza!

In short, tetraploids are complex and contain a lot of genetic material which can be immensely variable. Scientists doing genetic research on potatoes often choose to work with diploid lines instead, because tetraploids make such a muddle of their data it's hard to interpret anything.

So where does that leave you as a home gardener or small-scale farmer wanting to develop your own potato varieties? It leaves you in a position where you may as well have fun, experiment, use your imagination, be creative. As the results can't easily be predicted, you don't actually need to know anything about genetics. Think more along the lines of what you might get if you cross this colour with that colour, or this flavour with that shape - and then be prepared to be surprised!

One piece of misinformation I see spread all over the internet is a belief that you won't get anything worthwhile out of a home-made potato hybrid because producing just one good variety takes thousands of plants and many many years. This myth has arisen from under the slow-grinding wheels of the potato industry, which does work like that. Sure, if you want to breed a variety which will be listed in all the catalogues and sold in Tesco's and will make you rich from the royalties, your chances are very slim. The selection criteria for commercial potato varieties are immensely restrictive - and largely at odds with what most gardeners would want. Commercial breeders may well churn through (and reject) 200,000 seedlings to find one with commercial potential, then spend the next eight years doing field trials with it before it's ready for release. But don't let that put you off. You can breed a good variety within two years - easily. The majority of your home-made potatoes will be worthwhile, at least decent enough to eat and enjoy and feel proud of. A few will be exciting and wonderful. Even if you're only working with a very small patch of garden, you will almost certainly get some tubers that are worth saving and growing on next year.

The beautiful thing about potatoes is that it only takes two seasons to get a completely stable new variety. So it's actually quicker than most other vegetables. You make a pollination the first year and produce the F1 seeds, which are all unique individuals because of the genetic diversity. The second year you grow plants from those seeds and they make tubers. If you like the tubers, you simply propagate them by saving and replanting them. As the tubers are basically root cuttings of the parent plant (clones) they are genetically identical. There's no arsing about trying to make F2 and F3 hybrids (unless you want to) or years spent roguing out unwanted recessives. Once you've got something interesting, it's instantly a new variety.

Hybrid potato grown from TPS. This is one of Tom Wagner's hybrids, an F3 of Pirampo x Khuchi Akita. The parent varieties are Bolivian landraces, and are diploid.

If you've dipped a toe into plant breeding before, you'll know that plants tend to be either inbreeders or outbreeders - though that's more of a sliding scale than a polar absolute. Potatoes are really a bit of both. The natural status of potato is outbreeder. The various (diploid) landrace species from which cultivated potatoes are derived have a self-incompatibility mechanism which prevents them from pollinating themselves. The majority of diploid varieties are self-incompatible, although there are exceptions. This forces them to hybridise and mix their genes up in every generation, hence the wondrous diversity found among diploid landraces. However, when potatoes went tetraploid the compatibility barrier got screwed up somewhat. Many tetraploid potatoes have sterile pollen which can't fertilise anything at all, but others can fertilise themselves as well as each other. So they're designed to be outbreeders, but in practice a lot of flowers simply get knocked up by their own pollen.

Which gives you a choice: you can make hybrid seeds by crossing two different varieties, or you can make self-pollinated seeds which are the product of just that one variety.

Choosing parents: hybrid or OP?

Both are worth experimenting with, but for different reasons.

When a potato plant sets berries naturally without your intervention, it's most likely that it self-pollinated, but it may also have made hybrids with other potatoes flowering nearby, and you may have a mixture of selfed and hybrid seeds in the same berry. This is called open pollination (OP) … and the results are basically pot luck.

Making a deliberate hybrid is the most usual way to breed a new variety, as it introduces a lot more diversity. The basic method is to emasculate the flower to stop it from pollinating itself (which you don't even need to do if it's one of the many varieties with sterile pollen) and fertilise the female part of the flower with some pollen from a different variety. The offspring will be very varied, but that's the fun part and you should also get some hybrid vigour which makes for healthy and abundant plants. The only problem with this is that so many varieties of potato are poor berry setters, so not all varieties can be hybridised.

If you want to grow seeds from one specific variety it can be as simple as saving naturally pollinated berries from it, but if you want to be sure of getting self-pollinated seeds, it's easy enough to do (as long as it's one of the fertile varieties). Just dab a flower with pollen scraped from its own anthers, or other flowers on the same plant, or from other plants of the same variety. Bear in mind though that you will not get a true-breeding offspring of the parent variety by doing so. As potatoes are very heterozygous and have four lots of genetic material to throw around with cheerful abandon, even when they're self-pollinated they segregate into many different phenotypes. If you grow self-pollinated seed from Salad Blue, for example, you will not end up with a lot of spuds which look like Salad Blue. You will get varying shades of blue flesh, some much lighter than the original, some darker, and a few with pinky skin. If you grow selfed seeds from Congo, another blue variety, you may end up with a baffling range of purples, pinks and pure snowy whites, with considerable variation in tuber shape. What's happening is that all the genetic material which has been funnelled into the variety from various ancestors is segregating. Recessive traits emerge which weren't apparent in the variety you started with. If you grow enough self-pollinated offspring, you can start to build up a picture of the variety's pedigree, as many of the ancestral characteristics magically come back to life. So it can be a really fascinating thing to do.

A seedling grown from self-pollinated seed of Salad Blue. It's the only plant in the batch which has this striking black tinged foliage and black stems. I'm hoping it'll produce some dark tubers to go with it.

It's important to remember though that nature designed potatoes to be outbreeders, and if they self-pollinate they may show some degree of inbreeding depression. Only a bit though. As most spuds have such a rich and diverse genepool they can get away with a certain amount of inbreeding, but you may find self-pollinated seeds grow less vigorously than hybrids. That's not a problem and shouldn't put you off trying self-pollinated seed … but it's better to sow a few more than you need and then select the seedlings which show the most vigour and whoomph.

Variety differences

Differences in the fertility of individual varieties will most likely dictate what crosses you make, and how you do them. Over many years of being propagated by tubers, cultivated potatoes have moved away from the idea of flowering and producing seeds, and many of them can't be bothered to do it any more. Ironically for such a naturally variable and heterozygous plant, a historic lack of genetic diversity is thought to be the cause of the potato's fertility issues. The vast majority of modern cultivated potatoes are descended from one single Chilean spud, which had what is known as T-type cytoplasm, a genetic predisposition to making offspring with infertile pollen. Over the years many of these semi-infertile lines have been selected deliberately, as the male-sterility makes the process of hybridising them much easier. Consequently an awful lot of modern spuds have infertile pollen, and some are female-sterile too. Some can't be arsed to flower at all, and just dump their buds as soon as they appear. There are things you can do to force a reluctant variety to produce flowers, but it's a lot of hassle which I won't go into here, and from the point of view of future breeding work it makes more sense to choose varieties that at least show some willingness to come up with the goods.

I wish I could give a simple list of which variety does what, but I only know about the ones I've grown and observed myself, and it can vary from garden to garden anyway. Different countries have different varieties - import restrictions have affected exchange of material - so the ones I work with in the UK may not be available to people in the USA (just as most popular US varieties are strangers to me). So you will have to experiment with whatever you have available. As far as I can see, varieties fall roughly into four categories.

Some potatoes are very fertile and make excellent male or female parent varieties. Salad Blue is the Cassanova of the potato world - it only has to look at another potato and a berry starts swelling. You can usually tell a fertile variety because it naturally sets its own berries in profusion. Desirée is another very fertile one, and so is Mayan Gold, although the latter is a diploid so it needs to find the right kind of partner, or get lucky mating with a tetraploid.

Most cultivars fall into the male-sterile or almost-male-sterile category - these are the ones which flower happily enough but don't tend to set berries. Highland Burgundy Red is a good example of this, as is British Queen. It gamely produces a mass of dainty little flowers but in years of growing it I've never had a single berry. Give it a dab of pollen from a fertile variety though, and it sets berries very readily. So it makes an extremely good female parent. The advantage of male-sterile varieties is that you don't have to emasculate them, which makes it much quicker and easier to hand-pollinate them. Some varieties which appear to be male-sterile may actually be female-sterile. So it's worth trying the pollen on another variety to see if it will take. The disadvantage of using these partially sterile varieties is that it perpetuates the poor fertility of potatoes. If you want to do Solanum tuberosum a real favour in your breeding projects, select the progeny for good berry production. Because good berry production is what will keep its genetic heritage alive, as well as enabling some much needed new diversity to come in.

Then you have what you might call the awkward buggers category. These include Pink Fir Apple (syn. Rose Finn Apple) which not only has male sterility issues, it often can't be bothered to set a berry even when it's given fertile pollen. What usually happens is that the flower opens happily enough and you carefully pollinate it two or three times and on the third day the whole bloody thing drops off. Or worse, it starts to set a berry and then it falls off before it's mature. It pays to try again though, because there's a good chance that one of the pollinations will take eventually, when the plant is in the right mood and the planets are in the right alignment or there's an 'r' in the month. It's a pain in the backside to have to keep pollinating more flowers, but bearing in mind that each berry can easily produce 100 seeds or more, it only takes one successful pollination to give you loads of future breeding material - so it's worth persevering. Again, with a variety like this you don't need to waste time emasculating. I just go through the whole crop each day dabbing fertile pollen on every stigma I can find and saying "come on, set a bloody berry you sod!"

And finally you have the total refuseniks. There is a wonderful Victorian potato called Witch Hill which is reputed to be one of the best flavoured potatoes around - it is truly delicious. I would love to use it in breeding work. But every year the flower buds appear, and just as they're starting to look promising they drop off. All of them. Little dessicated posies cast to the ground. Now, unless it changes its mind, I cannot breed from it. If a variety won't flower, there is no breeding possibility, it's as simple as that. I could grow fields of the stuff and hope for a spontaneous somatic mutation, but that may never happen. Witch Hill is a genetic dead end. This is why breeders like Tom Wagner select breeding lines from varieties which are good berry setters. If a variety won't flower or won't set berries, it has no future.

The annoying thing is, Witch Hill did flower for me a couple of times when I first got it (it came to me as a laboratory-grown microplant) but I hadn't got into potato breeding at that time so I didn't think to make any crosses with it. D'oh!

Hybridising potatoes: the practical bit

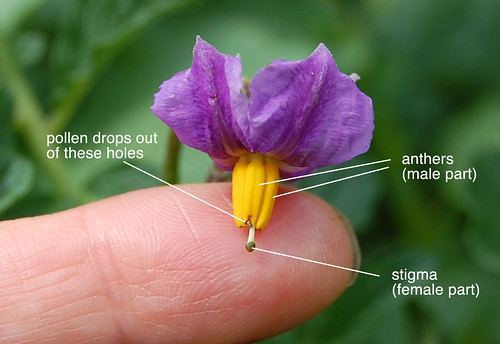

Let's be grateful for small mercies: potato flowers are nice and simple and easy to work with. They are 'perfect' flowers which contain both male and female parts.

Anatomy of a potato flower. Each of the anthers is a double sac, both halves containing pollen. When the anthers mature they develop little holes in the ends (like a salt cellar) and the pollen falls out onto the stigma.

The Mayan Gold blossom shown above is fairly typical, but there are variety differences in the exact shape of the flower. Some have a long style where the stigma protrudes some way out of the flower (be aware that a sticky-outy stigma has more chance of being cross-pollinated by passing insects than one where the stigma is hidden away). Some produce a neat little fused anther cone, others produce a rather grotty collection of misshapen anthers which don't hold together properly. Some (like Pink Fir Apple) do weird things where anthers and petals morph into one another. None of this matters - the principle is the same. You'll get to know the individual character of the flowers in your own garden as you work with them.

In order to control what pollen fertilises the flower, you have to stop the flower from fertilising itself, so that means removing the male parts of the flower before they mature. As I explained above, with some varieties you don't need to do this - if the variety produces sterile pollen or none at all, you can save yourself the trouble. The instructions shown here are for if you have a fertile variety or want to be sure of getting hybrid rather than selfed seed.

Potato flowers are produced in cymes - bunches of flowers which open consecutively, 2 or 3 at a time. The flowers last two to four days but tend to close up in late afternoon. The anthers develop holes in their tips when they're ready to dehisce, though they're not very glamorous - in fact they look more like some insect has had a go at them. Potato pollen is white, powdery and very fine. The stigma is receptive for about 2 days and the period of pollen shedding also lasts about 2 days. Fortunately for the garden dabbler, the female part tends to become receptive just before the pollen starts to shed, so you have a window of opportunity to intervene.

The best time for hand-pollination is in the morning when pollen is most abundant, and when the temperature is fairly cool. But I wouldn't worry too much about this, it works at other times too.

If you're using a variety with infertile pollen, or you aren't bothered about the chance of a few self-pollinated seeds, you can skip steps 2 to 4.

Step 1: Having chosen the variety you want to use as the female parent, find a blossom at the right stage. Potato pollen can be shed quite early, before the flower opens, so emasculation has to be done while it's still at the bud stage. What you're looking for is a nearly-ready bud where the calyx (outer green bit) has started to open but the petals are still shut. This is a variety with a sticky-outy stigma, but with many varieties it will still be hidden inside the petals. Doesn't matter either way, although a sticky-outy like this inevitably carries a small risk of picking up stray pollen from elsewhere.

You may notice a strand of mauve wool poking out underneath. I tied this around the stem of the flower (or in this instance the whole cyme, as I'm going to hand-pollinate all of them) as a marker, so I can be sure I know which ones I've hand-pollinated. I use a different colour of wool to indicate different pollen fathers.

Step 2: Peel back the petals and you'll find the anthers inside. They are still immature at this stage - with no holes in the ends. If they do have holes and are shedding pollen, try a slightly younger bud instead!

Step 3: Using a blunt scalpel blade, tweezers or similar, pull/scrape the anthers off, being very careful not to damage the style - the central stalk with the stigma at the end.

Step 4: After removing all the anthers you're left with a denuded female part, ready to be pollinated with the pollen of your choice.

Step 5: Next find the flower you want to use as the male parent. Choose a blossom which is newly opened, as those are the ones most likely to have a good pollen stash (the ends of the anthers should be open at this stage). Pull off a single anther using tweezers/scalpel/fingers.

Step 6: When you turn the anther over you'll see it has a seam down the back, separating the two pollen sacs. Additionally, each individual sac has a little slit down its centre. Carefully slip the tip of a blunt scalpel blade through the slit and slide it along. Note that the slit should be open so you can insert the blade freely ... you want to avoid cutting into the anther if you can.

If there is pollen inside, you will see it on the tip of the blade. It's a very fine white powder. If you don't see any white powder, try another anther from a different flower. You don't have to collect all the pollen at once ... just scrape out enough to dab on the female flower, and use the rest for more pollinations. (When the first sac is empty you can do the same with the other side. You can often pollinate ten or a dozen flowers from the pollen in a ripe anther like this.)

Step 7: Armed with your pollen-tipped scalpel, go back to the bud you just emasculated and dab the pollen powder onto the stigma - which is the knobbly-bobbly thing at the end. The stigma is mildly sticky when it's receptive, so you should find the pollen grains sticking to it quite readily. No need to make a song and dance with it - just a gentle dabbing so as not to risk damaging the stigma.

Step 8: The next day, go back to the same flower and pollinate it again with pollen from another fresh anther. The stigma remains receptive for around two days in total but you don't know exactly when that is, so for best results give it a pollen dab on three consecutive days. You'll notice that the petals have opened on this flower now, although it looks a bit weird as it has no anthers. Once the petals have closed and wilted a bit, you can assume it's no longer receptive.

Step 9: The berry starts to form. Yay!

From this point on, patience is the order of the day. Potato berries seem to mature painfully slowly. Try to resist the temptation to prod and poke them, you don't want them to fall off as they dangle clumsily on their alarmingly scrawny stalks. After about four weeks you need to watch for them dropping off naturally. Ideally, tie a little cloth or paper bag over them at this stage so that they are caught safely if they drop. Alternatively, be very vigilant, and ready to rummage about on the ground if you notice them suddenly go AWOL. Fortunately they don't taste nice enough for animals to be interested in them, at least not in the way of UK garden wildlife, so they're unlikely to be carried off, but you don't want to chance it.

One key factor about potato berries, significantly unlike tomatoes (to which they're closely related), is that the seeds carry on developing even after they've detached from the plant, and the berries will stay firm for months. This has several advantages. For one thing it takes the pressure off you to extract the seed from them ... you can leave them until you've got the time and inclination, even weeks or months down the line. Secondly it means that all is not lost if the berry is dropped too early or the plant dies prematurely. This is very significant in the light of the blight problems we are all besieged with. The plants can be struck down by blight, wither and rot - and the berries will still survive. Save the berries and let them mature, and as long as you clean them thoroughly they will yield perfectly healthy seed.

The topic of cleaning and processing TPS from the berries is to be the subject of a separate post. In the mean time, go out and make some berries!

With thanks to Tom Wagner and friends at the TaterMater forum for advice and suggestions (any errors are entirely my own responsibility).

54 comments:

Thanks so much for posting this. I am just beginning to get into potato breeding and you have answered some of my questions. I'll look forward to future posts on your potato efforts and, as always, your peas.

Rebsie, glad you are making a go of this. Your presentation is good, very good. Looks like I may be learning from you. Thanks for picking up where I left off.

Tom Wagner

I did it the easy way - self pollinated seeds of Salad Blue. As you say, they are very variable but I got two lines of potatoes I'm happy with and they're doing as well as can be expected in drought conditions!

Excellent explanation and pictures.

Thanks for that; I've just been looking at mine and wondering about a cross. Maybe Negresse and British Queen; it might give me a chance of an earlyish African queen!

Maggie - really glad you found it helpful. Best of luck.

Tom - nearly everything I know about potatoes I learned from you. Very pleased you stopped by. Your work is an inspiration.

Kath - I'm looking forward to seeing how those turn out!

Robert - ooh, African Queen, what a lovely idea. I'm growing Negresse too, but as it's the first time I've grown it I don't know what its pollen viability is like. Keep me posted on how you get on.

Another truly excellent post. If British gardens don't fill up with a wonderful diversity of home bred spuds, the gardening public are less adventurous than I thought.

Glad to see dirt under those fingernails. Your mum will cope.

I wonder whether "go and make potato berries" has any unexpected meaning in Quechua we ought to know about?

Thank you Owen. This is the straightforward bit, the practical side of it. I'm still psyching myself up for the article about diploids and tetraploids and how the twain shall meet in unreduced gametes. I'm having an interesting time researching it because all the relevant literature is behind paywalls where I can't access the full text. It's amazing what you can learn by reading lots and lots and lots of abstracts.

Hmm, my mum would do her nut if she saw those fingernails. I blame the camera for showing up my fingers in such hideous crisp detail. I didn't have this problem when I used a crap camera.

I expect the Quechua word for potato berry doubles as "put that camera down and go and scrub those disgusting nails".

I look forward to your diploids and tetraploids (and triploids?) post.

Surely one would expect "Daughter of the Soil" to carry the planet's most precious commodity around with her at all times. Where better than under her fingernails? I was actually looking for the tell-tale double line fingertip callouses that come from fretting the 12 string for hours on end.

Your efforts at popularising and democratising the art and science of plant breeding are bound to bear copious and delicious fruit in the years to come. A cliche perhaps, but true nonetheless.

Brilliant post Rebsie! The photos are great, and I like the dirt under the nails. I can never seem to get mine clean in June especially. You've inspired me to try some crosses this year.

Great post Rebsie!

Oooh Rebsie, potatoes! Now you're talking, you temptress. I might yet give it a go!

Thanks Rebsie - A brilliant post as usual!

I have some Desiree in the garden flowering now so may save some berries to see what I get :-)

Owen, thank you. Apparently potatoes don't make triploids very often, but they do make a lot of unreduced gametes, so the best chance of a diploid x tetraploid cross is to get an unreduced diploid to make a new tetraploid.

Despite my mum's best efforts I refuse to be ashamed of my earth-laden nails and I don't even own a nailbrush. The lack of 12-string callouses I am slightly more ashamed of because I don't practice the guitar very often any more. I'm spoiled rotten by my music partner who is actually a cellist but plays the guitar 100 times better than I do so it's easier just to let him get on with it.

Thanks for your understanding of what I'm trying to do - I see the same motivations underlying your efforts with Radix. The lack of plant breeding activity and consequent shrinking of biodiversity is entirely cultural as far as I can see. Why do people not breed potatoes? Because they don't know they can. Because they never even thought of it. Because nobody else is doing it, and therefore they assume it's difficult. I'm not arrogant enough to think I can change gardening culture, but I am sprinkling a few seeds.

Leigh - I know you have some wonderful stuff in your garden, so best of luck! It would be great if Blossom would set some berries.

Thanks Patrick, and thanks for your support by linking to me.

Mal - central and lowland Scotland is one of the best potato growing regions in the world, may as well make the most of it!

Jude - I only grew Desiree once, and it was a mass of berries. Hopefully yours will give you plenty of seeds to play with next year.

This is fantastic! I'm a long way from getting into potato breeding, but I'm fascinated by the process and wondering if one day I shall be able to breed an early potato that likes my heavy soil ...

Hi Rebsie

I think there are a couple of triploid potatoes around - chaucha (S. stenotomum x S. andigenum) and rucki (S. x juzepczuckii). Those names may be out of date.

I can see a fertile hybridization between amateurs and mainstream science. They can do all the tedious stuff and we'll have all the fun.

Allotment blogger - it shouldn't be difficult ... just save some berries from an early variety, grow the seeds and see which seedlings thrive in your heavy soil.

Owen - ah yes, some of the 'species' types may be more prone to triploids. I have a couple of stenotomum hybrids I'm playing with this year, which I'll be using in both diploid and tetraploid crosses so I'll see what happens. Not sure how you can tell when you get a triploid though. Hmm, I feel another mammoth reading-of-abstracts session coming on ...

Let's hope blight stays away a little longer. One day of rain - no more.

Good luck with your crosses.

The enigma of triploid potatoes by G E marks 1966 - might be a good place to start - anyone have a Euphytica subscription?

BTW Will you be selecting for blight resistance a la Raoul Robinson?

Now you've shown the way, and pointed out the advantage of mixing up diploid and tetraploid ... this weekend, Mayan Gold shall meet Negress. I visualise a black-skinned, golden-fleshed tater, black and yellow striped chips, or perhaps a black and yellow piebald potato!

Am I right in thinking all of the tuberosum/phureja crosses (Mayan Gold is one, but I have a couple of others) are diploid?

Owen - thank you for that suggestion. I have read Raoul Robinson's potato breeding book but his method of recurrent mass selection is not going to work for me unless somebody bequeaths me a field. I am however doing some blight resistance trials on a much smaller scale. I have some hybrid and OP seeds of John Tom Kaighin, one of Tom Wagner's varieties which has been bred for good blight resistance and excellent flavour. It's being grown in Europe for the first time this year by me and a few other people, so we'll see what happens. When it flowers I'll make more hybrids with it and see if I can get the blight resistance genes spread around a bit.

Ian - to the best of my knowledge, Mayan Gold and the rest of the Mayan series are diploid. A cross with Negresse is a lovely idea ... I think dark skin is dominant, so I don't see why you shouldn't get some lovely black and gold combinations. Crossing a diploid with a tetraploid is not as easy as doing a tetraploid x tetraploid cross, and you'll probably have to make quite a lot of pollinations to get it to work. As I was saying to Owen, diploid potatoes are very prone to making unreduced gametes (i.e. a doubled genome) which is no doubt how they became tetraploid in the first place ... it varies between varieties but can be 1 or 2%. What that means in practical terms is that you will only get a few berries, and even in a successful berry you will find only three or four seeds instead of the usual 100+. I know that sounds like a lot of work for not very much, but on the plus side, each viable seed will be a stable tetraploid. More importantly, these diploid x tetraploid crosses are the best way to get some much needed new genetic diversity into potatoes, so it's a really good thing to do.

I crossed Mayan Gold with Salad Blue this year and have got one berry out of about six pollinations. More would be better but I ran out of flowers!

You can make the cross both ways (assuming Negresse has fertile pollen - Mayan Gold certainly does). It might be difficult but I think it would be worth it.

Lovely, pro pics & descriptions, Rebsie!

I'm going to have lots of TPS and real potato seed this autumn, so check out my website then for a swap.

Hy Rebsie,

Thanks for your great and helpful post. Unfortunatly I've been given you link too late for this season for good crosses and polinization.

I'll see the results of the seeds I got finally. I've posted some of their pix on the forum of Tom wagner.

Talking of Tomatoes here. I had a terrible year with them last year, the "looked-after" greenhouse ones just rotted on the plant before they were even ripe enough to do anything with, but my 4-year-old son's outdoor-in-a-pot "introduction to gardening" tomatoes just stormed ahead, and we had the best fruit from them!

I am hoping for better this year....

breeding own potatoes is very nice. thanks that you share us that how we can breed potatoes. very amazing.

backyard design

I just love your blog!!! I'm breeding some tomatoes and potatoes myself and it's one of the most exciting things i can think of! Glad to see I'm not the only one...

Thanks for the information and knowledge.

Keep blogging.

I'm interested to know what developed from the hybrid with dark (black) stems and darkly tinged leaves.

Have you tried collecting pollen by vibrating the anthers with a tuning fork? This works with all the solanaceae family. I use an 'E' tuning fork which is about the average frequency used by european bumblebees. The pollen puffs out and can be collected in, e.g, film canisters, spice jars etc. and if kept really dry, stores for weeks or months in a fridge; allowing you to cross varieties that flower at different times.

Thanks here you share nice information about potato breeding and having different variety of tomatoes,I inspire by your work.

Buy flowers online

Your article pushed me today to try and cross pollinate 2 of 3 types of potatoes currently growing in our garden: German butterball and an unknown white potato with pink-splashed eyes and purple flowers. -pardus pilot in Texas

I was able to get at least 1 potato berry from German Butterball. Go me. -pardus pilot

Your article making me to try pollinate with these type of potatoes instead of getting from online shopping, Great explanation with pictures

Rebsie,I like the way you have presented your thought and research here,very compelling to read you.Buy Online

Hi..one question. Can potatoes be grown from fruit seeds.I grew what I thought was a fruit trees and got potatoes instead. Not going to give full story. But I know where it all started and came from now I have a potato variety from a fruit. I didn't eat any of them and got them to seed and planted them today. 9/3/17 and hope I get more potatoes or a fruit plant...crazy. cheers

Thanks for the information. Once very beneficial to us all. Awaited further information.

Cara Mengecilkan Perut Buncit

Manfaat Slimming Capsule

Manfaat Slimming Capsule

Manfaat Slimming Capsule

Slimming Capsule

Khasiat Gastric Health Tablet

Great post, it was really interesting. Do you know if there is some kind of list to check which varieties are fertile? I bought this year Violetta (Blue Elise)end red Emmalie but I have no idea if they are fertile or not...

regards

Just wondering what methods you can use to get a poor pollen producing variety to produce pollen Thanks Anthony

From where did you purchase your Witch Hill microplants and/or microtubers?

Thanks.

hi Im giving a talk on hobby breeding of potatoes next month in and I wonder if I could use some of your potato breeding photos in my power point ,Ill of course give you credit for them.

Im david langford and i had 300 varities in my back garden and have breed a small amount for myself .

googlr david langford+potato to check me out

thanks

please reply to langford527.dl@gmail.com

Thanks for the information.

Thanks for the information.

Not found elsewhere.Very clear and informative.

Dr.V.N.Reddy

Not found elsewhere.Very clear and informative.

Dr.V.N.Reddy

Very interesting. This might be a stupid question, but could a tetraploid be fertilised by two diploids to produce fertile seeds? In the same way that some varieties of apples require two types of pollen.

How long does it take a pollen to be ready

Pardon for replying. I wonder if boron (liquid form) application will help to boost the plant reproduction. Can research on this. Plant needs this to grow and produce well. Hope this helps.

Found you via Pinterest. This has become a weekly meal in our house. thanks for the recipe.

That was absolutely fascinating, thank you!

i have often seen berries form on different varieties in my garden (north east Ireland) but never even considered trying to grow a new plant from them. My Orlas in the tunnel have berries on them at the moment. This is an absolutely Terrific Blog. Will have to read further. Best wishes and keep up ypur great work!

Roisin Cotter

Tissue culture mother plant produce flower????

Post a Comment